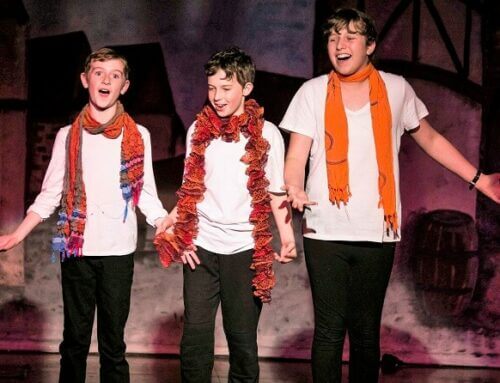

Picture twenty excited, nervous, Year 5 students, a lake, a bridge of pallets and planks of wood. I say ‘bridge’ loosely, as the pallets and planks are merely laying on one another. More alarmingly, some are floating away or sinking. My students are excited and nervous because we will be attempting to cross the ‘bridge’.

I love unexpected, authentic learning and am always looking for experiences offering this. This bridge crossing was a fun challenge that, on the surface, encouraged risky play – it also became the year’s most memorable maths class.

During this Dhumba-dha biik, the Year 5s discovered that the Secret Second Island would become a place for wildlife only. We had been visiting it recently because due to the drought, the lake bed had dried up and we could reach this otherwise inaccessible island. The students were disappointed at the prospect of losing access to this place, but recognised its importance for wildlife. My colleague suggested we say goodbye to this much-loved area, which would involve crossing the ‘bridge’ and, recognising the importance of risky play, I could not pass up this opportunity.

In the preceding weeks, there had been substantial rain and the lake was now about 60% full, meaning waist-deep water. It had been raining since my colleague’s class had visited, so we knew the lake would be deeper and the bridge slipperier. Some of his students had fallen in and we could easily be next – I said, “Let’s think about the maths.”

Where possible, I like to weave maths discussions into Dhumba-dha biik. I asked my class, “What are the chances we will all make it across the bridge?” ‘Likely’, ‘unlikely’, ‘impossible’, ‘possible’, ‘certain’ were tossed about as they assessed our class. “What chances do you give yourself to make it across?” Responses varied, with some quietly telling me they would fall in. I made it clear that the crossing was optional. “What percentage of the class will make it across?” After some quick mental calculations, the consensus was 75-80%.

As we walked to the bridge, I heard discussions about how deep the water could be. Some students picked up sticks to determine the depth of the lake. There was chatter about individual success, possible crossing strategies, being a risk-taker and ‘giving it a go’.

Leading by example, I confidently stepped on to the structure, which immediately started to sink, much to my class’s delight. As I moved across the perilous structure, I reassured them (and myself!) that the bridge was sinking because of my weight. I declared I probably weighed at least double what they weighed and that the bridge would not move so alarmingly during their journey.

Some students demanded to know how much I weighed and, once I told them, there were swift calculations to determine if this was true. They also began reassessing their chances of crossing, based on their mass.

Slowly and carefully, the class commenced their trek. I stood in the middle, praying I wouldn’t be submerged. I held their hands, encouraged and directed them across the bridge. The first few students made it across successfully and guided the others using their knowledge of position, depth, direction, mass and angles.

We successfully traversed the bridge with a 100% success rate and said goodbye to the space we loved. The students were far more confident on the return trip, however, this led to speed and lack of attention. They soon discovered that the faster you went, the more likely you were to slip, and the bridge began to claim its victims.

Once everyone was safely back on dry land, we reflected on our predictions. We had been correct that it was unlikely our entire class would make it across. Our original prediction was that 75-80% of us would be successful and we were pretty close, with a 72% success rate.

The entire experience, intended to be risky play, was actually one of unexpected maths: weight, depth, angles, mass, speed, volume, capacity and displacement, along with mental computation. I could not have covered all of these concepts within my classroom in such an authentic, engaging and fun way, nor would the class have been as memorable!

The outdoor environment is ideal for rich, authentic mathematics, and if you can add a touch of risk-taking to it, you have an unforgettable, powerful learning experience.

Samantha Millar is a Year 5 classroom teacher and Outdoor Learning Coordinator at Cornish College. She is passionate about getting children outside and connecting them to their land and country. You can follow her on Twitter @mrs_sammillar.